FINAL SELF-PORTRAIT DRAWING OF STANLEY SPENCER ACQUIRED

The last known self-portrait drawing of Stanley Spencer — executed a few months before his death in 1959 — has been acquired by the gallery dedicated to his work in his hometown, Cookham, Berkshire.

The work, which has been purchased with the support of Art Fund on behalf of the Stanley Spencer Gallery, as well as The Band Trust, The V&A Purchase Grant Fund and The Friends of Stanley Spencer Gallery, was conceived as a work in its own right before he painted a version in oil, now owned by Tate Britain

The drawing is showcased as part of the Stanley Spencer Gallery’s current exhibition, LOVE, ART, LOSS: The Wives of Stanley Spencer at the Stanley Spencer Gallery (until Autumn 2021), which explores the relationship between arguably two of the most important figures in the artist’s life —his two wives, Hilda Carline and Patricia Preece.

Says a spokesperson for the Stanley Spencer Gallery: ‘This is a very important addition to the Stanley Spencer Gallery, and we are grateful to the generous financial support of the Art Fund on behalf of the Stanley Spencer Gallery, as well as The Band Trust, The V&A Purchase Grant Fund and The Friends of Stanley Spencer Gallery.’

Jenny Waldman, Director, Art Fund, said: ‘Spencer’s striking self-portrait offers a unique perspective into the final months of this important British painter. We are delighted to support the Stanley Spencer Gallery in this acquisition, ensuring the work goes on public display in Cookham where the artist was born and found such inspiration.’

The oil painting was commissioned by friends of the artist, Joy Smith and her husband, and is the ultimate expression of the Spencer’s talent in that it not only a true likeness, but also hints at the uneasy dialectics which must have been at the forefront of a dying man’s mind.

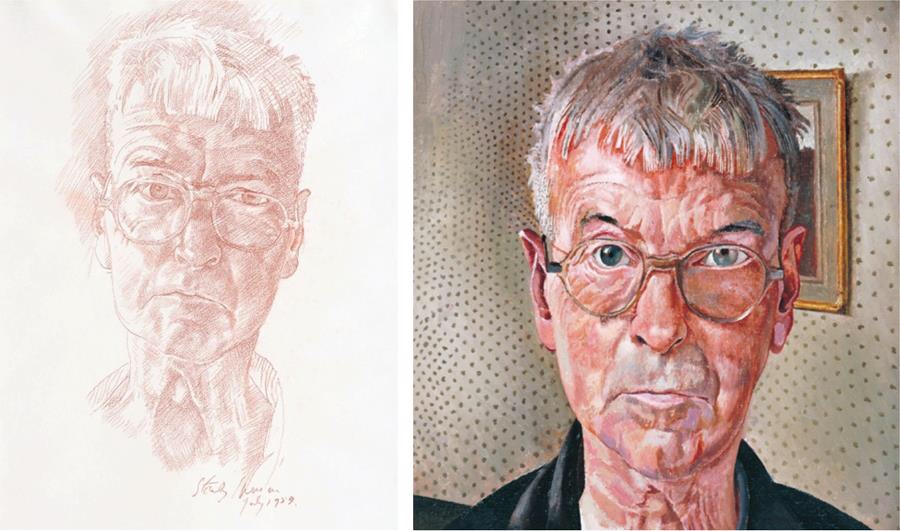

Spencer drew the self-portrait in red conté while observing himself in a dressing table mirror. Conté is a harder, waxier medium than pastel, which creates a finer impression more suitable for portraits. The artist’s gaunt, weathered face is overwhelmed by the frame of his glasses.

Yet the deep wrinkles of the forehead, the sagging flesh of his neck, and the grim, sloping downturn of the mouth are offset by a determination and strength found in the unflinching gaze of his right eye (his left eye squints as he searches for a clear image of himself in the mirror), and the resolute set of his eyebrows.

It is an intense, unnerving image, its immediacy of line expressing the frailty of the sitter. It is unmistakably Spencer, with the sharp fringe running across his forehead, a style he wore all his life. The artist has used loose, parallel hatching in the background in order to project the image towards the viewer, but on the face itself, he has created depth and contrast with tight cross-hatching, as he was taught to do at the Slade School of Fine Art in the manner of Michelangelo.

Spencer had a close relationship with the Smith family, who owned the self-portrait. He frequently visited their home in Yorkshire, and later executed an oil painting of Joy along with additional portrait sketches of Joy’s two sons and her husband. Their relationship, and the eventual realisation of the portrait, is charted in a comprehensive document written by the Smith’s daughter, Catherine, based on correspondence with Spencer, notes left by Joy, contributions from Spencer’s daughters and the writer’s own recollections.

In a letter dated 16th February 1959, we hear the first mention of the possibility of Spencer executing a self-portrait: ‘I know I have promised it but it may never be done all the same. When I went into hospital, I realised that I must do only the work that I wished to do’. When Spencer’s cancer went into remission, he embarked on what would be his last visit to Yorkshire. On 8th July, he met Joy at the Great Northern Hotel and had lunch before taking the train north. He wrote that month: ‘I think late lunch at the Great Northern sounds romantic. I’m all for that, only no hurrying for the train mind.’ Shortly after arrival, he drew the present sketch at Joy’s request.

In the event, Joy Smith was not happy with the resulting image. She apparently — and surprisingly — did not find it a true likeness, but it is more likely that she found it too uncomfortable. Days later, she and Spencer went to Leeds where he bought canvas and oils to paint another version, underdrawn in red conté, which is now at Tate, London, but originally hung in the dining room until 1982 when the house was sold. It is certainly a tamer, diluted and easier image with which to live. The oil medium has subdued the immediacy, vigour and raw emotion of the present sketch in which the weight of mortality bears down upon the sitter.

Only two months after that work was completed, Spencer was in the Canadian Hospital in Taplow, Buckinghamshire, not far from Cookham, where he was born and lived for most of his life. After a short remission he returned to hospital in December, where Joy visited him. According to her notes, they discussed ‘the nature of inspiration and the importance of physical form as a source of inspiration and love’ — a conversation whose essence must surely be found in this self-portrait, at once a triumph and a resignation. He died shortly afterwards of cancer aged 68.

The Stanley Spencer exhibition, which features the drawing, has proved a huge succees. ‘Since re-opening on the 15th August, we are very pleased to report that we have had a nearly normal number of visitors for the time of year,’ says a spokesman. ‘Many of our visitors have said how pleased they are that we have re-opened when so many galleries and museums remain closed or have limited opening times.’